|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rinpa Painting and the Revival of Heian Aesthetics

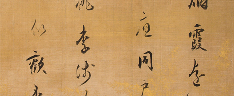

Rinpa is a movement of painting and aesthetic design that emerged in Japan during the Edo period (1615–1868). Kyoto-based artists Tawaraya Sōtatsu (fl. early 17th century) and Honami Kōetsu (1558–1637) are acknowledged as the predecessors of this artistic tradition, one that harkens back to the court paintings and calligraphic works of the Heian period (794–1185). Rinpa is characterized as a revitalization of Yamato-e, Japanese-style painting developed in the 9th century characterized by a rich palette of colors, softly contoured landscapes, emphasis on themes drawn from poetry, and primarily secular subject matter.[1] Works falling under the category of Rinpa consist of mostly paintings but also include lacquer ware, ceramics, and textile designs. Rinpa is regarded by some as “quintessentially Japanese,” especially when compared with Japan’s Chinese-influenced schools of painting.

In a sense, Rinpa also served as a political movement, emerging at a time when Japan’s political and military capital was moved from Kyoto to the city of Edo (modern-day Tokyo). Because of a concern that Kyoto might suffer the same fate as the ancient capital of Nara (710–794), a strong commitment was made to preserve the imperial capital as the center of Japan’s artistic and cultural development. Rinpa works, which revived the grandeur of Kyoto’s courtly classical past, attracted the attention of the Edo period’s emerging merchant class. These townspeople wore Rinpa-style kimono and decorated their living spaces with Rinpa folding screens, hanging scrolls, and fans, essentially aligning themselves with Heian-period courtiers.

Kyoto townspeople continued to find pleasure in recognizing the classical themes and motifs used in Rinpa designs. However, the Rinpa style was redeveloped when brought to Edo, and Heian-period references were no longer a priority for artists practicing in this mode. Instead, Rinpa evolved into an aesthetic style movement with a greater emphasis on its decorative qualities than on the extravagance and depth seen in earlier works.[2]

Artists working in the Edo period who followed the aesthetic trend set forth by Sōtatsu and Kōetsu include Kitagawa Sōsetsu (active 1639–1650), brothers Ogata Kōrin (1658–1716) and Ogata Kenzan (1663–1743), Sakai Hōitsu (1761–1828), and Suzuki Kiitsu (1796–1858). The term “Rinpa” was an invention of the 20th century; during the Edo period, the movement was mostly referred to as the “Sotatsu School” (Sōtatsu-ha). Hōitsu conducted a personal study of the works of Kōrin, and it was Hōitsu’s preference for his paintings that led to the adoption of the name “Rinpa” (“school of [Kō]rin”) in the late Meiji period (1868–1912).

The three major painting techniques most associated with Rinpa are tarashikomi, horinuri, and mokkotsu. Tarashikomi (“dripping in”) refers to the application of pigment onto an already wet surface to give a running, pooling effect. The term Horinuri (“painting-by-carving”) refers to the technique of leaving gaps in an otherwise densely painted section, rendering the impression that the paint has been carved away, used to create lines of untreated and uncovered paper or silk. Lastly, mokkotsu (“boneless”) is the application of pigment in a manner that covers form-defining outlines, so that the object depicted appears to have been rendered solely through the application of paint. Unlike other traditional painting schools organized along teacher-student lineages, Rinpa is based on a shared appreciation and application of its associated aesthetic, with no reliance on artist pedigree. Anyone could be a Rinpa painter simply by working in the Rinpa style.

– Erika Enomoto