|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

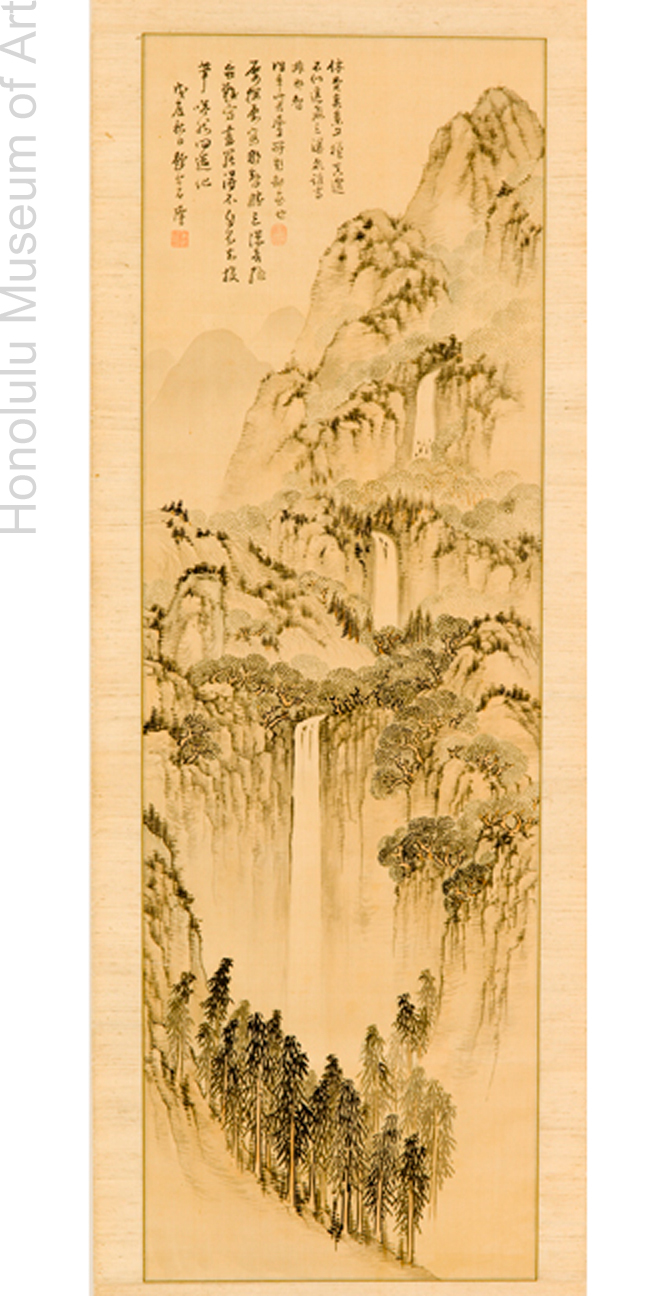

Noro Kaiseki (1747–1828)

Nachi Waterfalls

Japan, Edo period (1615–1868), 1808

Hanging scroll; ink and color on silk

Gift of Terry Welch, in honor of Howard Rogers, 2005

(13170.1)

Shinkeizu (“true view picture”) is a mode of literati landscape painting that developed in China. Despite the name “true view,” these paintings are a reflection of the artist’s visceral experience of a particular place, rather than an accurate depiction of the actual site. Shinkeizu tested the artist’s ability to go beyond the appearance of his or her subject in the production of a highly personalized interpretation of a known landscape. This genre of landscape became popular among Japanese literati painters in the 18th century, including Noro Kaiseki (1747–1828), an occasional student of Ike Taiga (1723–1776), who was an early painter of “true view pictures.”

As he relates in his posthumously published treatise Shihekisai’s Talks on Painting (Shiheikisai gawa, 1829),[1] Kaiseki’s representation of Nachi Waterfall, an important spiritual and cultural site located in Kii Province (modern-day Wakayama Prefecture), achieves his goal to render a painting taken from “the true landscape within one’s own mind.” The artist first visited Kumano, the site of the falls, in 1798, while serving the daimyo of Kii Province. The location was particularly significant for Kaiseki as it enabled him to express both his pride in Kii Province’s natural beauty as well as his deep interest in literati culture.

Nachi Waterfalls demonstrates a compositional type known as “Three Waterfalls in One View,” which combines three mystical panoramic views in one painting. The composition leads the viewer’s eyes from the pine trees located at the bottom of the painting, diagonally upwards through the waterfalls, finally arriving at the mountain peak in the upper right. Depth and distance are shown by layering mountain forms one atop another, and through atmospheric perspective, whereby lighter ink tones are used to approximate the haziness produced by intervening mist; both are typical features of Chinese-style landscape paintings.

Literati artists were highly capable but it was essential that their work exude an amateur quality, as revealed in the inscription accompanying this painting, a conversation between the artist and a friend on the challenges of painting shinkeizu. The inscription clearly conveys the artist’s humble appraisal of his own abilities as a painter.

Don’t waste time painting a true view.

You might copy the form yet not capture the spirit.

As for the three waterfalls cascading in the distance,

Who can say it is not Nachi?

In the past, a friend inscribed this on my humble painting.

Many times I visited, and many times I painted the view of Nachi.

The magnificence of the three waterfalls is the most difficult to depict.

Even when the painting is finished, I do not know if I captured its spirit.

I throw away the brush with a sigh and ask the creator [why is it so difficult].[2]

– Erika Enomoto

[1] Wylie, Hugh, “Nanga Painting Treatises of Nineteenth-Century Japan: Translations, Commentary, and Analysis” (PhD diss., University of Kansas, 1991), 18.

[2] The translation is provided in Berry, Paul and Michiyo Morioka, Literati Modern: Bunjinga from Late Edo to Twentieth-Century Japan (Honolulu: Honolulu Academy of Arts, 2009), 89.