|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

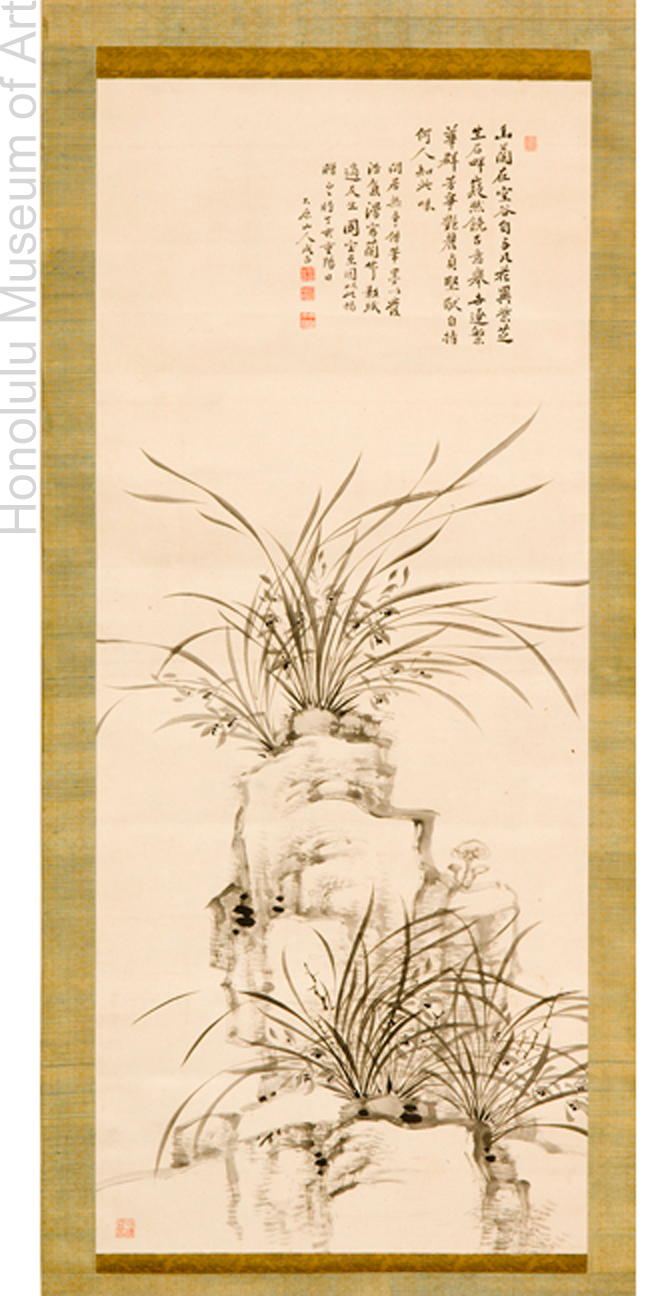

Nakabayashi Chikuto (1776–1853)

Elegant Orchid

Japan, Edo period (1615–1868), 1827

Hanging scroll; ink on paper

(13174.1)

In early modern China, the orchid, with its elegant and graceful appearance and its delicate fragrance, came to symbolize the principled, refined gentleman who sought the pleasures of a quiet life. Alongside bamboo, chrysanthemum, and plum, the orchid is celebrated in literati painting as one of the “four gentlemen,” and like that of the other three, the physical structure of this flora makes it an ideal subject for an ink painting. Many believe that the sense of fluidity and balance in calligraphic lines of such a painting can reveal the moral and aesthetic nature of the artist.

The long sweeping orchid leaves are the highlight of the painting, demonstrating the artist’s ability to execute a single, extended stroke through the unified, choreographed movement of his arm, hand and brush. The modulated lines created in this way not only capture with surprising accuracy the appearance of the orchid’s pliant leaves, they also convey the artist’s skill and transform the orchid into a symbol of that artistic refinement.

The poem in the top right corner reads in part:

Elegant orchid exists in a quiet valley,

Distinguishing itself from ordinary flowers.

Purple fungus grows at the foot of the rock,

Lofty and full of ancient sentiments,

The whole world pursues extravagant display,

Multiple fragrances vying for the florid beauty.

As for steadfastness and purity orchid alone possess them—

Who can understand this beauty?

In my leisurely life, with no special affairs, I borrow brush and ink to express my understanding,

I sketch orchid and bamboo on several papers.[1]

The painter of this work, Nakabayashi Chikutō, was a doctor’s only child. Chikutō began studying painting at the age of 13, and by adulthood, was well versed in the Chinese classics. His paintings often demonstrate his deep understanding of the brushwork traditions of China’s literati masters.

– Charise Michelsen

[1] Berry, Paul and Michiyo Morioka. Literati Modern: Bunjinga from Late Edo to Twentieth-Century Japan, 188.